The battle of the Linge,

a hell on the heights

When a peaceful landscape becomes a battlefield

Le Linge: Hunters' Tomb

The Battle of the Linge took place from July 20 to October 16, 1915. A peaceful mountain landscape was transformed into a field of chaotic desolation. Men turned this bucolic place into a hell of little or no strategic interest, where the lives, the flesh and the minds of too many French and German soldiers were shattered, more than 6,000 of them never to see their families again.

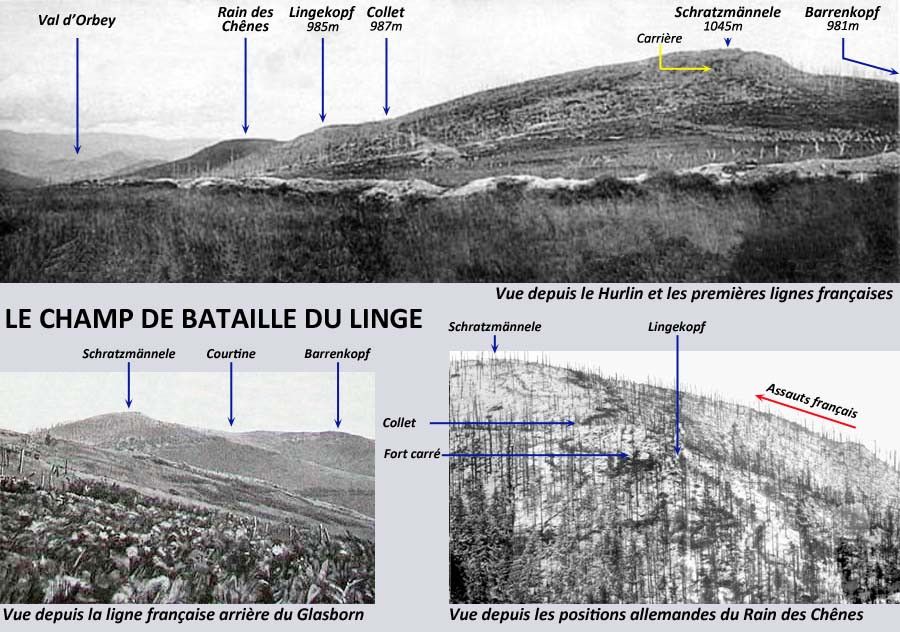

The Battlefield

The Linge massif is a mountain chain running parallel to the main Vosges ridge, from which it is about 6 km away as the crow flies. Its average altitude varies between 900 and 1100 m. From north to south, you'll find the Lingekopf (overlooking the Val d'Orbey), the Collet du Linge (where the path linking the Col du Wettstein to the Trois Epis passes through), the Schratzmännelé (Schratz as it was christened by the French soldiers), the Courtine, the Barrenkopf and finally the Kleinkopf (which alone offers excellent views of the Munster valley). It is approximately 3 km long.

The Linge and Schratz have steep wooded slopes covered by forest. They overlook a grassy, very wet valley, the starting point for French attacks. The Courtine links the Schratz to the Barrenkopf; here, the wooded ridge is preceded by a wide, gently sloping area of open grassland.

From the outset, French soldiers found themselves in an extremely difficult position due to these topographical conditions.

The situation at the front before the battle

By the early days of August 1914, the French army had entered the Munster valley, overrunning the small German force. However, at the end of August, French units were ordered to withdraw to the border on the great ridge of the Vosges. A large part of the Alsatian army was then transported to the Marne, where it took part in the battle that halted the German advance towards Paris.

In the Fecht valley, the very loose front more or less stabilized, with the French occupying the ridges and the Germans established further east in the valley. At the end of 1914 and beginning of 1915, however, Joffre wanted to resume the offensive in Alsace. He advocated a large-scale pincer movement around the Munster valley towards Colmar, combined with an attack on the plains from positions occupied further south by the French army. However, his intentions were thwarted by the German army.

In February 1915, the German army launched a violent offensive in the Fecht valley, with the aim of pushing French units back to the 1914 frontier. It then settled on the Linge chain.

Further south, the German advance in the Upper Fecht threatened the links between the 66th Division (which occupied the heights overlooking the St Amarin valley) and the 47th Division, which was in charge of the part of the front dominating the Munster valley as far as the Col du Bonhomme. In view of this situation, the two French divisions went on the offensive together in the spring of 1915, forcing the German units to withdraw from their positions, and finally conquering Metzeral in June 1915 after fierce fighting. However, Joffre persisted in his idea of taking Munster via the Linge.

The battle

The beginnings

Given the situation of the battlefield, the French army had to overcome enormous logistical difficulties. Starting from scratch, it had to build roads, camps, ambulances and first-aid posts, transport ammunition and supplies by mule, install heavy and light artillery, build battery emplacements, shelters and other necessary installations, and transport combatants, all in full view of the German enemy .

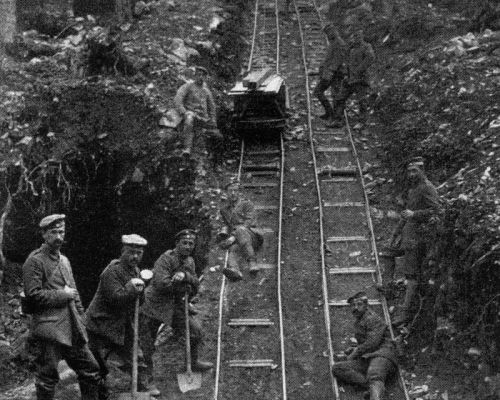

Faced with such preparations, the Germans did not stand idly by, preparing for the onslaught to come. Taking advantage of the shelter of the forest, excellent logistics (notably a narrow-gauge train from Les Trois Epis) and the proximity of the Alsace plain, German troops set up solid defenses. Trenches, dugouts and connecting trenches were set up on the mountain, fortifications built, pillboxes and machine-gun nests constructed, and fields of barbed wire unrolled along the steep slopes between trees, rocks, brambles and other chevaux de frise. These defenses added to the complexity of the battle for the French forces, and further accentuated their initial disadvantage on the ground.

The forces at work

On the French side, responsibility for the attack was entrusted to the 129th Infantry Division, commanded by General Nollet. This newly-created division comprised an infantry brigade and the 5th Chasseurs Brigade, made up mainly of young recruits from the class of 1915, many of whom had never seen fire. The 129th Division was reinforced by the 3rd Chasseurs Alpins Brigade, made up of veterans of long combat in the Hautes Vosges and Lorraine, detached for the occasion from the 47th Division. The artillery consisted of 220 (set up against the slope of the great Vosges ridge), 155, 120, 75 and 65 guns set up in batteries on the flanks of the great ridge facing the Linge range.

The Linge front was covered on the German side by units of the 6th Bavarian Landwehr Division (1st and 2nd Infantry Regiments), which belonged to the Haute Alsace army detachment commanded by General Gaede. They were reinforced during the battle by various units, including the Garde Jäger Bataillon, the 14th Mecklenburg Jäger Bataillon, the 73rd and 78th Reserve Infantry Regiments, and the 187th and 188th Infantry Regiments. German heavy and field artillery was mostly concealed on the Rain des Chênes ridge, behind the Linge range.

The course of the battle

French attacks

After several postponements, the French offensive was launched on July 20, 1915 by battalions of the 3rd Chasseurs Brigade. The plan called for an attack from the flanks, on the Linge on the left and the Barrenkopf on the right, followed by the Courtine and Schratz in the center. But the French artillery's destructive bombardment was of very limited effectiveness, as the German defenses hidden by the forest remained virtually intact. The attack launched at 2pm was a failure; caught under a deluge of fire, the Alpine hunters came up against a wall of steel; despite their fierce determination and incredible courage, they had no other resource than to protect themselves as best they could until nightfall. By evening, back on their starting lines, the elite French units had lost more than a third of their strength in just a few hours of fighting, and often many more!

On July 22, the young units of the 5th Chasseurs Brigade were thrown into the furnace. They returned totally decimated. The French attacks continued stubbornly over the following days, resulting inlittle progress on the ground and ever-increasing losses. French units finally reached the first German trench line on the ridge, but their positions were precarious and constantly under enemy fire. They would go no further.

On both sides, men suffer from the horror of combat, but also from hunger, thirst and fear of the constant threat of death.

Fierce attacks and counterattacks follow one another, and the small quarry on the Schratz is successively taken and lost by both armies. Soldiers from both sides were within metres of each other, and the grenade and bayonet battles caused bloodshed. The loss of men was considerable, and the situation of the survivors was miserable, an absolute horror. As the fighting wore on, the battlefield was transformed into a chaos of trees, stones and rocks smashed by artillery, a land upturned by shell holes and poisoned forever, a jumble of destroyed trenches, collapsed shelters, a field of horror strewn with decomposing corpses and wounded French and Germans waiting in vain for unlikely help, despite the great courage and dedication of the carers.

On July 28, Joffre decided to call it a day and ordered the withdrawal of the 129th Division (effective from August 20, 1915) and most of the artillery (heavy and field), leaving the already hard-pressed 47th Division to bear the full brunt of the battle.

German controffensives

On August 3 and 4, the Germans launched an intense artillery bombardment. It is estimated that over 40,000 shells fell on the French lines. Counterattacks followed one another throughout August, with French units holding out bravely.

On August 31, a terrible German bombardment rains down again on the French lines. Throughout September, the German attacks are repeated. For the first time on the Alsace front, the German army uses tear gas and flame throwers.

The horror of the battlefield became total. The 47th Division, left alone in the field and deprived of most of its artillery, lost over a thousand men in the fighting. Little by little, the French units were forced to withdraw. On October 16, the last large-scale German assault took place, but it was not easily repulsed. The lines then froze for good in a deceptive semblance of calm, with exhausted units from both armies returning to their original positions.

From the end of the battle to the armistice

After October 1915, the chasseur battalions were gradually withdrawn from the Vosges and replaced by line infantry units resting on a Vosges front that had become secondary. Units of Indochinese riflemen and American army units were even assigned there. Both sides went to ground, and the Germans transformed their lines into an impregnable fortress, which they christened "Fort Lingekopf".

But right up to the end of the war, the Linge remained a dreaded point of friction for combatants from both armies. Hand-to-hand combat, grenade exchanges, machine-gun fire and artillery bombardments followed one another on a daily basis. On average, five men were killed each day until the end of the war. The front was falling asleep, but the sleep was as restless as it was bloody.

The Linge, a human tragedy

The Battle of the Linge, of no strategic interest what soever, was a human tragedy marked by the courage, determination, self-sacrifice and sacrifice of French and German soldiers. It bears witness to the brutality and difficulty of fighting in the First World War, where thousands of lives were wasted for often minimal territorial gains.

The human toll was indeed heavy. On the French side, around 3,600 men died and some 8,500 were wounded. For the Germans, losses are estimated at around 8,500 men, including some 2,500 dead and 6,000 wounded (these figures are uncertain due to the destruction of German military archives in 1944-45). A thousand combatants from both sides were reported missing during the three months of intensive fighting, and several hundred of them still lie side by side in the earth of this so-called Field of Honor, which is an open-air cemetery.

The Linge was indeed " the tomb of the hunters ", as the German soldiers called it, but it was also the tomb of their enemies at the time.

Today, the site of the Battle of the Linge is a place of remembrance, where the remains of the trenches and fortifications built by the madness of men are preserved. May it serve as a reminder of the courage, suffering, sacrifice and memory of the French and German soldiers who lived, fought and lost their health or their lives here. Together, they deserve our utmost respect and consideration.